Belvederes

MIROSLAV MAKSIMOVIĆ, POET, ABOUT THE FATE OF A WORLD WITHOUT GOD OR POETRY

Searching for One’s Own Language

Every citizen of Europe is a European. Europe is not only the European Union. It’s not politics, but culture, faith, ethics and other common values. The homeland (state) is today the main, and perhaps last, defender of uniqueness of personalities and nations, as well as the defender of culture, which cannot exist without uniqueness. That is why the ”steamroller of globalization” considers culture the main obstacle on its way to the mindless and mass consumer society, which, as we know, hasn’t got spirit or poetry, the supreme expression of authenticity

By: Vesna Kapor

Photo: Guest’s archive, Marija Đorđević

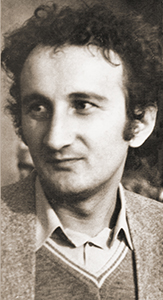

Poet, publicist, editor. Tracker and cultural emissary. And again, after all, a poet. Always timeless in his opus, ready for the grain of doubt in everything, which ultimately confirms great poetry. By following time and space in historical changes and dealing with the hidden, Miroslav Maksimović reveals the importance of small ordinary things. He notes the universe of an individual in the overall establishment of existence. In his latest book Pain, he uses sonnets to liberate poetic silence and long suppressed consciousness of a nation.

Poet, publicist, editor. Tracker and cultural emissary. And again, after all, a poet. Always timeless in his opus, ready for the grain of doubt in everything, which ultimately confirms great poetry. By following time and space in historical changes and dealing with the hidden, Miroslav Maksimović reveals the importance of small ordinary things. He notes the universe of an individual in the overall establishment of existence. In his latest book Pain, he uses sonnets to liberate poetic silence and long suppressed consciousness of a nation.

”Who will write a poem about this?” you say. Is that the crucial question, essence of the world: reflecting in a poem?

It’s not whether the world reflects in a poem, but whether a poem can make the world from something. So-called reality doesn’t have anything to do with it (it has, but its role is passive), poetry is reality. By the way, these are words of Stevan Raičković. In August 1972, four poets sat together (Stevan, Radonja Vešović, Rajko Nogo and I) in an olive orchard on Žanjice beach near Herceg-Novi, drank, snacked and talked. Suddenly, an olive tree next to us fell with a crash. For more than a hundred years it grew and gave fruit, and then decided to collapse in the presence of poets. As if it expected the poets to make a new reality from it. Stevan immediately asked the question you mentioned, but almost forty years passed until one of us wrote a poem about that event. However, this is already a new time, olives don’t collapse in the presence of poets, but in the presence of wood traders.

IMPRISONED IN THE MATERIAL

What changed in the world and poetry since your first collections of poems?

What changed in the world and poetry since your first collections of poems?

Changes in poetry (and art in general) have taken place ever since it exists: one form of expression becomes outdated and a new sprouts from it. Every new poet must find his own space in order to be a poet. That is the change in poetry. However, a new poet doesn’t just fall from the sky; he’s related to what’s already been created in poetry, thus changes in poetry are the same as changes in the life of people and nature: new life keeps appearing, but it’s still the same life.

However, I think that changes in the world, or in people’s social life, differ from changes in history up to now. The entire history of mankind is a story about gaining and losing freedom, a battle for overcoming limitations of the material world and those of the human society organization. All discoveries in natural sciences and conclusions of social sciences were created from that battle, the space of freedom increased. That means that human spirit was the forerunner of the human battle for freedom. Today, however, everything is led by the material surrounding of human life; spirit lags behind it. In such an atmosphere freedom is limitless, but in fact it doesn’t exist at all: you’re imprisoned; the material is limited by its nature and doesn’t permit stepping out onto the belvederes of the impossible, which is the spice of the idea of human freedom. Without spirit, which opens those belvederes, there’s no freedom. Without spirit, the human society lacks (basically) human effort to overcome his limitations. There’s no God. Thus, (basically, in the so-called developed, rich society) there’s no poetry either. It doesn’t mean it won’t exist: I won’t say that the fate of mankind depends on the fate of poetry, but I’ll say that the fate of poetry is an indicator of the fate of mankind.

What was the relation between traditional and modern during the time you’ve been writing in? And how do you personally experience and interpret that relation?

What was the relation between traditional and modern during the time you’ve been writing in? And how do you personally experience and interpret that relation?

If understood as finally determined categories, into which everything alive in literature is placed, then traditional and modern don’t have a meaning, except for literary-political discussions and disputes. External characteristics of modernity and traditionalism – according to them, modern is what isn’t as it used to be, and traditional is what is as it used to be – can be used in such discussions, but they will not lead to the essence of art. I tried to explain what modernity essentially is on the example of Dušan Radović: he is one of the founders of modern expression in contemporary Serbian poetry not because he wanted to be modern, but because he had the need to go beyond the outdated and exhausted forms of creating, where one cannot breathe any more, and reach a new, his own language. The same can be said about traditionalism: if it’s authentic art, its recreation, new creation on the bases of old forms – which means searching for a new, one’s own language. Accordingly, classifying into traditional or modern isn’t a way to valorize a literary work and truly interpret it. After all, such classifications are often incorrect and superficial. To go back to Dušan Radović: his poetry has traditional folklore elements, although his works are considered an example of modern poetry.

FROM THE HEAD OF THE ENTIRE NATION

One of your poems is ”Loving Serbia”. You’re one of the rare people who understand that the country (state) is something more important and more permanent than politics and other passions, and that it can be subject of poetry?

One of your poems is ”Loving Serbia”. You’re one of the rare people who understand that the country (state) is something more important and more permanent than politics and other passions, and that it can be subject of poetry?

That poem quotes verses of Oskar Davičo, Tin Ujević, Jovan Dučić, Vladislav Petković Dis and Dositej Obradović, that is, they are weaved into the text. They’re a kind of a coauthor and they all have poems about Serbia. Therefore, poets with such a subject are not so rare in the history of literature. Your conclusion could be more valid for the present time. In that aspect, there is an interesting detail: when you see dates the poems of mentioned authors were made, you see it was a time with hope. Perhaps there are less such poems today because there’s less hope.

Why would today’s poet be interested in patriotic subjects? Well, it happens, due to actual events, that the homeland-state is the main, perhaps only and last defender of uniqueness of individuals and collective/nation, correspondingly the defender of culture, without which uniqueness doesn’t exist. The steamroller of so-called globalization – the process, except positive moments, hides pure exploitation of the weak – attempts to flatten all differences, both individual and national. The main obstacle on the path of that steamroller is culture, therefore it attempts to remove all differences and fit it into the environment of mass consumer society, which, as we know, hasn’t got poetry as the supreme expression of uniqueness, authenticity. So, when singing about patriotic subjects, a poet sings to defend poetry. Furthermore, it is understood that a good patriotic poem is before all a good poem. If it’s bad, it neither contributes to patriotism nor to poetry.

Drawing Reality is a collection of poems close to latest events. It contemplates the contemporary world, politics, history? Personal and national at the same time?

That book (that name is better than ”collection” – because I write books, I don’t create collections of poems written in the period since the previous book) was created from 2008 to 2011. So, it was written in Golubac, where I practically live since 2008, still formally remaining a citizen of my home city of Belgrade. Since I was able to watch Serbia from the inside, not from the Belgrade distance, that book, according to my opinion – perhaps an illusion – is all made of Serbia today. That’s why it has so many ”coauthors”, people of different vocations, education, sex, living and dead – who helped me write certain poems in different ways. While writing, I knew I needed them, but I didn’t know why. When the book was published, Marko Paovica explained, to me as well, that it’s a way to say that the book is ”from the head of an entire nation”.

HISTORY, LIFE, POETRY

The poem ”Blowing of Winds” testifies about something important, without pathos: ”... if you are a Serb/ next to the heart of Europe/ if you are curious/ like any European...”?

The poem ”Blowing of Winds” testifies about something important, without pathos: ”... if you are a Serb/ next to the heart of Europe/ if you are curious/ like any European...”?

The question suggests my non-poetic answer about the relationship between Serbs and Europe. So, here it is. Serbs are Europeans, just like any other inhabitants of Europe. Different from others, mainly due to their history, but no more and no less Europeans than others. Europe is not just the European Union, as the common political-media speeches suggest. Europe is from the Atlantic to Ural, as De Gaulle defined its borders. Europe is, therefore, full of cultural, religious, economic and political varieties, and the only thing that can make it united is the wish of all European nations to establish together, in agreement, harmonious mutual relations and relations with others in the world. They need supranational organizations for it, but only for coordination, not as political authority. The main problem of the European Union today is that it’s overly based on politics and too little on common European values. It didn’t even succeed in putting the undoubtedly common value such as Christianity into its statute. We must, therefore, strengthen our state regardless of the European Union, think about Europe as a realm of culture, and the European Union as a realm of politics. Each of us is, hopefully, aware that the European Union thinks about us only politically; values, the so-called ”chapters”, are only a convenient excuse, but not crucial: this is proven by many countries admitted to the EU at a time they were far below all standards which Serbia already fulfills today. It means that they were admitted due to politics and not European values.

Can a poet avoid the history of the collective, the history of a nation?

Can a poet avoid the history of the collective, the history of a nation?

Can any man avoid history? No. You cannot escape history. There is no place you can hide. Because history is life. Life has its course, chaotic and unpredictable, and history is made when we try to give that course a meaning, systematize it and establish a kind of order. That is where history and poetry touch and immediately diverge. They both have a relationship with life, but completely different. History shows, with facts and documents, what happened in life and how, while poetry shows nothing, it’s an experience. A poet cannot avoid his life, and his life is also the history of (his) nation, but he creates poetry from life, a new life, without describing previous life as history does. I stated several times, as example of the relationship between history and poetry, Raičković’s sonnet ”On a September Beach in Herceg-Novi in 1991”: history has its documented story about that time in that area, but we’ll feel its essence much better from the experience in Stevan’s sonnet. Similar can be said for my book Pain – I suppose it was the reason for this question.

In the accompanying text to your book Pain, we see that your mother’s suppressed trauma was growing in you your entire life?

Pain came to me by accident, coincidence, but it was obviously prepared on the unconscious level for a long time. A smart man said: coincidence is a way of God to hide his presence. I’ve got nothing to add. As for the social context, I believe that consciousness of the genocide suffered in the XX century is maturing in the heads of Serbs. Therefore, we shouldn’t push the story to oblivion, allegedly for the sake of future, or put it on the war flags of revenge, but cherish the awareness of it – through the educational and cultural system – so it’s present in our lives, both practically and symbolically, because it’s a necessary element of our future’s basis. The story about the future makes sense only if it relies on elements of the past, if it builds the dignity of its own being. Otherwise it’s only an empty political story about an empty future, which brings only emptiness, not a fulfilled life. s

***

Circle

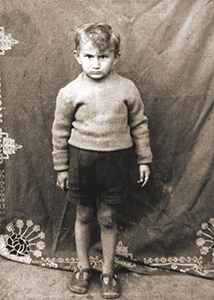

Miroslav Maksimović was born in 1946 in Njegoševo, Bačka, from father Milo from the Drina and mother Stoja from the Una. He lived in Belgrade since his birth, but spent shorter periods in Sarajevo, Zagreb, Knin and now Golubac. He worked in the Literary Youth of Serbia, Literary Association of Serbia, BIGZ, was part of the editorial board of ”Literary Word”, ”Literature”, ”Bestseller” (editor in chief). He published about a dozen books of poetry (the first was ”Sleeper under a Blotting Pad” in 1971 and the latest ”Pain” in 2016), three books of essays. He won all important Serbian awards for poetry and this year, for ”Pain”, as much as five awards.